Spain's Civil War is INSANELY Interesting. Here's Why.

The Spanish Civil War has often been called the “dress rehearsal for World War II”. And yet, this consequential and fascinating conflict is something many of us have never even heard of.

I recently uploaded this video to my YouTube channel. However, I adapted the script as a long read below. Enjoy!

Here’s a nice, long read on the reasons people should find the Spanish Civil War fascinating. Soon, it will also be available in video form on YouTube.

Don't let the word 'war' fool you - the political and social aspects of Spain's Civil War are the focus here.

If you find yourself inspired to read, here is a post with books I recommend.

The Spanish Civil War 1936 to ‘39 has often been called the “dress rehearsal for World War II”. And yet, this consequential and utterly fascinating conflict is something many of us have never even heard of. Absurd.

For Spanish people, it was a conflict of ideological extremes: monarchists, nationalists and fascists, supplied by Hitler and Mussolini, who rose up against the 2nd Spanish Republic, a coalition of socialists, communists and anarchists, supported by Stalin’s Soviet Union. Thousands of Americans volunteered in the Abraham Lincoln Brigade. The British Author George Orwell joined the fight too. Even JRR Tolkien and C.S. Lewis had opinions about it.

I’ve covered Spain’s Civil War for years - I even filmed a mini-doc in Madrid years ago. And I’m convinced more people would be obsessed with it too if they just had someone advocate for it passionately. I want to infect you with the same passion that I have - showing why it’s relevant for everyone, everywhere right now.

Starting with: Fascists vs. Communists

You can begin to understand the War’s modern relevance with a look at the outrageous political polarization of the time. The 1936 Spanish General Election must be the craziest in all of history. I’m serious. When you cast your ballot in 1936, you had the actual choice of voting for a party inspired by German and Italian fascism. Floating-head fascism not your cup of tea, how about the communist party? You like the extreme, but not the authoritarianism? No problem. Cast your ballot for the independent anarchists! Spanish voters must have felt whiplash going down their ballots.

I don’t want to overstate the case. There were centrists in the mix too. But the extremes in 1936 carried significant political power and influence in Spain, and the election would lead these poles of ideology to Civil War within months.

Why was Spain so divided by 1936? Well, centuries of declined empire and hardship for ordinary people produced two things: different answers about how to revive Spain to its so-called golden age, and various political powers fighting to implement their solution. Spain had gone from running the largest empire since ancient times in 1600 to losing almost everything by 1900 (5,xv). A few of their last major colonies - Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Guam - were handed over to the United States after the Spanish-American War in 1898. (5,apx5;(5,39))

Back in Europe, Spain spent the 1800s like many countries: balancing their monarchy with liberalizing forces. They even briefly became a republic in 1873. When that experiment was ended, the 1876 Constitution created a constitutional monarchy under Alfonso XII. But ideologies were simmering - the Russian Revolution of 1917 inspired Spanish Marxists and terrified conservatives who saw their Catholic monarchy under threat.

These fears led King Alfonso XIII to turn a blind eye when General Primo de Rivera staged a coup in 1923. Rivera's dictatorship suspended the Constitution but ultimately fell apart during the Great Depression. The King, who had "acquiesced" to dictatorship in 1923, demanded its end in 1930 (2,24-28). But this brought about his own downfall - into the power vacuum came a surge of republican sentiment. After local elections showed large anti-monarchist feeling in 1931, Alfonso XIII went into exile. The Second Spanish Republic was born, young and vulnerable.

That vulnerability was made worse by anger. A government of the new Republic managed to upset just about everyone. Prime Minister Manuel Azaña's coalition from 1931-1933 slashed the size of the military, initiated land redistribution, supported women's rights, and reduced the power of the Catholic Church. Article 3 of the new Constitution even declared "The Spanish State has no official religion."

The political right was furious. Wishing for Alfonso XIII to return from exile and reclaim the throne, Lieutenant general José Sanjurjo led a failed military coup d'etat in August 1932 (3,1-2).

But the right weren’t the only ones angry. To many on the left, Azaña wasn't radical enough. Sure, he reduced Church power - but did he actually burn churches down like some anarchists? No! He initiated land reform - but did he support full collectivization like his socialist colleagues? No! To the left of Azaña were many who thought he didn't go far enough in tearing down Spain's power structures.

Prime Minister Azaña barely scraped by for a couple years before more elections in 1933. In these, the pendulum swung the other way. A right-wing coalition won and took power, which reversed most of what Azaña’s government had done. You start to see the back-and-forth. This caused an intense reaction on the left, which reorganized itself and initiated strikes. The most notable was an anarchist-led miners uprising in Asturias that was put down by the military. At least fifteen hundred died and tens of thousands were imprisoned (2,136).

This was the insanity of Spanish politics before the Civil War. While elections were still happening and power transferred somewhat peacefully between left and right, political violence was everywhere - churches burned, priests murdered, right-wing officers staged coups, a leftist uprising ended in massacre. The stage was set for something larger and darker.

I think you can now imagine the disparities of the 1936 election, the last before everything changed. To increase their odds of taking power, most parties of the left and right joined in large coalitions that would cooperate if victorious.

On the right you had the National Front, its largest member was CEDA (Confederación Española de Derechas Autónomas). Its leader, Gil Robles, inspired by Musollini and Hitler, also emulated their campaign materials. The core of CEDA and the Spanish right was conservative Catholicism; generally this also meant a restoration of the Spanish Monarchy.

There were two kinds of monarchists in Spanish politics. The Alfonsists and the Carlists. I actually had a call with a friendly historian to help me distinguish them. Alfonsists, as the name implies, wanted Alfonso XIII to retake the throne, but beyond that, their politics were more moderate, classically liberal. Carlists were monarchists too, but wanted a different king; it’s not worth diving into who - more important is that Carlists were more active conservatives. Antony Beevor called them “arch-conservative” (14,42). As my new friend put it, they were the ‘keep Spain great again’ folks. King, church, a dash of populism, though usually not too radical.

Speaking of radicalism, the Falangists, Falange Española, were the most explicitly fascist group in the 1936 elections. Their leader was Primo de Valera. If the name sounds familiar, it’s because this was the son of the dictator we spoke of earlier. The Falange Party actually didn’t perform well during the 1936 elections, but is worth mentioning because of who would go on to join its ranks: General Francisco Franco. He’s important and we’ll mention him again soon.

So on the right you had nationalists, explicit fascists, footsie fascists, monarchists (both Alfonsist and Carlist), conservative catholics, industrialists and landowners. The blending of these into political parties made up the National Front.

On the left you had the Popular Front, Frente Popular. The name of the coalition itself, Popular Front, was derived at an international communist conference: the 7th conference of the Comintern. And so, yes, the Spanish Communist Party was within the Popular Front. There were also standard parties of the left, the socialists were there, as were left-wing republicans and a trade-union workers party. Catalan nationalists were under the Popular Front umbrella too.

There were other flavors of Marxists present, like the National Confederation of Labor, CNT, the largest force of anarchists in Spain. And the Workers' Party of Marxist Unification, POUM, which we’ll return to when we speak about George Orwell.

So on the left you had secular socialists, communists, anarchists, regional nationalists, and left republicans. The blending of these made up the Popular Front.

In February 1936, the National Front, the right-wing coalition, was victorious in these areas:

Winning along the outside of the map and in the dead-center around Madrid, was the Popular Front. Official results gave the win to the Popular Front, but it was a contested and narrow victory.

So two governments ago we had a left-wing government that changed a bunch. Then in 1933 we got a right-wing government that cancelled everything. Now in 1936 it’s another left-wing government that’s gonna change it all back. It’s just so wobbly. And now it falls over into war.

As the leftists of the Popular Front began planning their time in political office, officers in the military were already planning the next coup. On July 17th, 1936, General Francisco Franco and his experienced Army of Africa began an uprising in Morocco. The next day, garrisons across Spain made decisions about whether to rebel or remain loyal. Meanwhile, the government began distributing weapons to trade unions and independent militias ready to defend the Republic. The Spanish Civil War was underway. As the commander of the Spanish Foreign Legion put it: ¡Viva la muerte! ‘Long live death!’

Don’t worry. I’m not about to put little toy soldiers on a battle map and give a play-by-play of the War. We will resist the pull of the military history industrial complex.

Rehearsal for World War II

But now that we know why the prelude to the War is interesting, what’s so interesting about the War itself? The Spanish Civil War is known to this day as the staging ground for World War II, the ‘dress rehearsal’ for the most devastating war in all human history. That’s because the War did not remain a domestic affair. Several powers intervened in Spain, attempting to bring their preferred side to victory, while giving their armed forces practice for a future global conflict.

One of those powers was Nazi Germany. Initial German supplies for the Nationalists were ferried into Spain through Salazar’s Portugal (14,116). But this support became far more direct when Adolf Hitler accepted a personal letter from Francisco Franco, and came to the decision above his advisors and bureaucracy to intervene with manpower, planes and other materiel (1).

Not only did Germany send planes and tanks for Franco to use, he sent some of his own Air Force, Luftwaffe, to gain experience in Spain. They were called the Condor Legion - and in just a second we’ll see their acts of terror are not forgotten in Spain even today.

While Germany’s Condor bombing raids were devastating, those made by Franco’s Italian allies were larger in volume and more decisive. Bombing raids in Barcelona would help bring about its fall to the Nationalists in early 1939, a clear sign of the end (14,332). But even from the start, Italy’s leader Benito Mussolini was enthusiastic to support Franco and the Nationalists. Just two weeks into the uprising in 1936, Italian assistance was on its way through the Mediterranean (14,135).

In total, about 500 million dollars of fascist financial support went to Franco, along with 100,000 German and Italian soldiers to serve directly in Spain on the side of the Nationalists (15).

The Republic received outside intervention too, though less than international sympathy would suggest. While the Republican Government was seen by western democracies as the legitimate government, Britain and France had policies of ‘non-intervention’, as did other European countries and the United States (14,132). These attempts at neutrality weren’t airtight, but served to weaken the Republic's position, while their Nationalist rivals got help from fascist Germany and Italy loud and proud.

Unlike the Nationalists, who received over 100,000 soldiers from Germany and Italy, the Republic had nothing on this scale. So in order to match the volume of Nationalist forces, the Republic relied on foreign volunteers - just individuals who decided to show up and help without permission of their home governments; I’ve seen numbers totalling 50 to 60 thousand internationals who made their way to Spain through unofficial channels to serve in militias and specific foreign brigades. The International Brigades came from Russia, France, the UK, the US and Canada, even Germany and Italy - the list goes on. (18;4,160).

The anti-fascists who joined the International Brigades played a major role in the War. For example, 2,000 of them participated in the Battle for Madrid in 1936, which prevented its fall to Franco until the end of the War. So assured was the Republican Government that Madrid would fall in 1936, that they relocated the Capital to Valencia. So assured were the Nationalists that Madrid would fall, their radio stations announced Gen. Franco had already made it into the center of the city on a white horse.

But the International Volunteers combined with civilians and anarchist militias to hold Madrid’s line through the end of 1936. This forced Franco to switch strategy. Instead of a quick invasion, he had to siege Madrid for two years. This was a massive setback that delayed his complete victory, and a massive psychological victory for the Republic. It wouldn’t have happened without international brigades.

Back to nation-states, one often forgotten supporter of the Republic was Mexico, which sent rifles and ammunition. As Spain’s agricultural output collapsed, Mexico supplied food (14,331).

But by far the largest support for the Republic came through the Soviet Union. Joseph Stalin was slow to aid the Republic, beginning only with fuel exports (14,139). Military supplies began trickling in in the fall, but rival deliveries from fascist governments had already been arriving for months. The Soviets officially had 2,000 soldiers on the ground, more clandestinely (15).

The Soviet and Comintern support for the Republic totalled in the hundreds of millions of dollars. In turn, though smaller in number, Spanish communists came to the forefront of the defense of the Republic, as reliance on Stalin deepened. Soviet support dwindled as the situation worsened for the Republic. As the Spanish national bank’s supply of gold and silver ran low, the Soviet became more stingy, even with loans (14,331).

If it’s not already obvious, I’ll spell it out. The ‘rehearsal for World War II’ is reflected through the actions of the international community in Spain. While countries like Italy and Germany aggressively pursued another fascist state in Europe, Britain and France were hoping they could ignore the whole thing through appeasement until it went away. The USA practiced isolation, though firms sold equipment and oil. The Soviets were as minimal in their support for the Republic as they could be without losing face, only to have their hand forced by developments in the War. I’m not one for basic boy military history, but that sounds fairly on-brand for all these countries, stage-setting for something truly awful on the horizon.

As George Orwell wrote, his fellow English were “all sleeping the deep, deep sleep of England, from which I sometimes fear that we shall never wake till we are jerked out of it by the roar of bombs.” His prediction came true in the London Blitz.

We’ve looked at the big-picture through ideology and foreign powers. But in my opinion you can’t truly develop a passion for learning about Spain’s Civil War until you zoom in and find people that interest you. For me, that person is George Orwell.

Writers and Spain

Orwell is best known for his works Animal Farm and 1984. While ‘Orwellian’ has become a catch-all for political rhetoric we find distasteful, and Big Brother a misunderstood symbol used to sell Apple Computers in the 1980s, Orwell’s real politics are subtle and independent. And his tragic time in Spain helped develop his worldview into something that would influence discourse through today.

Orwell chose to live out his values by fighting fascism during Spain’s Civil War. And with ‘fight fascism’, I don’t mean show up and protest. I don’t mean lollygag in Madrid while printing Spanish Republican propaganda (looking at you, Earnest Hemingway). I mean literally fighting fascism in a militia, which Orwell joined upon arrival in Barcelona. His story of doing so is brilliantly and accessibly detailed in his book Homage to Catalonia (8).

Towards the beginning is Orwell’s most straightforward description of his motivation for going to Spain and fighting for the survival of its Republic. He writes, “For years past the so-called democratic countries had been surrendering to Fascism at every step.”

Orwell took the precarious trip through France and over the border into Catalunya with a vague sense that it was time to take a stand as an anti-fascist. Britain, his liberal democracy, wasn’t acting, so he would. Upon arrival in 1936, Orwell was enchanted with the classless vibe in Barcelona, which was dominated by anarchists.

So he joined the ranks of an independent anarchist militia - we mentioned them earlier, the POUM, the Workers' Party of Marxist Unification. While the Spanish Republic was leaning further and further on Joseph Stalin’s Soviet Union, Orwell joined a militia that was anti-Stalin.

Orwell became disillusioned as time dragged on. The POUM’s training was terrible; the militia’s structure was anarchist like the party’s politics, so officer orders could be questioned by any rank. And I don’t know if this really counts as disillusionment, but Orwell got shot in the neck.

And this was when it unraveled. As he recovered from his wound back in Barcelona, Republican infighting took hold. In 1937, communist influence in the Republican Government was at its peak and reorganization was taking place to bring independent militias to heel - to purge those not in conformity with Stalin’s influence. Orwell’s POUM and other anarchists found themselves under fire in the streets of Barcelona as they resisted integration. (16) Soon after, Orwell fled the country.

Orwell arrived with optimism and left under fire from republican allies. This experience gave Orwell a clearer vision of his politics. He later wrote: “Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic socialism…”

Totalitarianism obviously included Nationalists and fascists, Orwell took up arms against the far right. But his perception of totalitarianism is also a critique of Communism under Joseph Stalin. Through this we can read Animal Farm and 1984 with greater understanding. This is, as Christopher Hitchens titled his book, Why Orwell Matters.

Orwell wasn’t the only writer to take an interest in the Spanish Civil War. We already mentioned the inferior Ernest Hemingway, who wrote For Whom the Bell Tolls, a fictional account of an American volunteer who is tasked with blowing up a bridge in the Sierra de Guadarrama mountains northwest of Madrid. J.R.R Tolkien, author of the Hobbit and Lord of the Rings Trilogy, argued his preference for Franco’s Nationalists with his friend C.S. Lewis, who disapproved of the uprising. (1)

Indeed, while the Spanish Civil War is mostly lost to public imagination today, buried under World War II, it was a hot topic of its day.

Picasso: Painting a Bombing

It wasn’t only writers. Artists of many kinds expressed their feelings about the war, including Pablo Picasso, who was inspired by a truly awful event.

On April 26, 1937, Hitler’s Condor Legion bombed the Basque town of Guernica (2,620). They fired, rounded, and repeated until 100,000 pounds of explosives were dropped over three hours. Accounts are disputed, but somewhere between a hundred and a thousand died (4, 289). Many civilians were mowed down by strafing planes; others asphyxiated in shelters, deprived of oxygen by the raging fires.

The intent was clearly the intimidation of a people, a terror tactic carried out indiscriminately. The New York Times published a contemporary account by correspondent George Steer which described the “demoralization of the civil population and the destruction of the cradle of the Basque race.” (19)

In Paris, Pablo Picasso decided to paint. “In the panel on which I am working,” he said. “which I shall call Guernica...I clearly express my abhorrence of the military caste which has sunk Spain in an ocean of pain and death." (22)

This is what he produced, a colossal canvas which stretched 25 feet wide and over 11 feet high. When I was a teaching assistant in Spain, I had the privilege of taking several of my fourth-grade classes to the Reina Sofia Museum to see it. The black, white and grey paints give glossless life to horrific imagery.

Fearing Nazi invasion of France, Picasso sent Guernica to the United States Museum of Modern Art in New York. The painting, he demanded, was not to reside in Spain until democracy was restored. The move was prudent. Paris was occupied in June 1940. A German gestapo officer, rummaging through Picasso's studio came upon a photo of Guernica’s creation process. “Did you do this?” the officer asked. Picasso’s reply is perhaps apocryphal. “No. You did.” (20;21).

I sometimes wonder if our visit to see Picasso’s painting had an impact on those students. They’re old enough now to participate in the cultural battle over the Civil War and Francisco Franco that continues in Spain today.

Because after winning the Civil War, Franco was Spain's dictator until dying peacefully in his sleep in 1975. I spoke with a couple older Spaniards while living in Madrid who said things like ‘at least things were orderly’ under the dictatorship. When I filmed my mini-doc there, I recorded bullet holes at the University City in Madrid still unrepaired from the Battle of Madrid.

I regret this, but I also visited Valley of the Fallen during my time in Spain. It’s a sanctuary built into the side of the Sierra de Guadarrama mountain range, the same one Hemingway wrote about in For Whom the Bell Tolls. The remains of at least 30,000 civil war victims are buried there, and at the time I visited, so was the late Gen. Franco, whose corpse mingled with Nationalist and Republican fallen alike.

As you might expect, this place is absurdly controversial. Franco was exhumed there in 2019 after a protracted legal battle, and there was an effort by the socialist government in 2020 to secularize the site through a "Democratic Memory Law".

Speaking of democracy, Spain democratized after Franco’s death, but a desire for Franco’s politics never went away. In 1981, an attempted coup d'état in the Spanish Congress tried to stop democratization in its infancy. Today, as Europe lurches to the political right, new Spanish political parties like Vox are reopening historical debates about the nature of the Civil War and Franco’s regime.

But I told you the Spanish Civil War is not just relevant for Spaniards. Make no mistake about it…

the Spanish Civil War has lessons for all of us.

I live in Washington, D.C. And so I took a walk on the campus of Howard University. Among a long history of this University, Vice President Kamala Harris gave her 2024 election resignation speech here. This is also where a pre-med student named Thaddeus Battle, yes his real name, decided to leave this side of the Atlantic in 1936 to join the Abraham Lincoln Brigade in Spain. He received an injury during his service to the Spanish Republic, but was able to return home to the United States (23).

And I don’t know the full story of Thaddeus, so I won’t use his memory as a prop. But he wasn’t the only American who went over and fought in Spain. There was a sense that history swayed on a hinge. To control the future one had to push or pull.

Doesn’t it feel that way now? I don’t mean a cheap point about the back-and-forth of elections. I produced a digital event a few years ago with Adam Tooze, and he used the term ‘polycrisis’ - multiple massive challenges for humanity at the same time: war, climate, threats to democracy. If you’re like me, you feel lost in it.

The more I read and learn about the Spanish Civil War, the more I see it as the opposite of what it seems. At a glance, the War appears to be the clash of great and confident ideologies - the masses divided into camps with conviction to fight. And conviction was present, otherwise so many wouldn’t have fought.

But when I look again, I see also lost people just grabbing on.

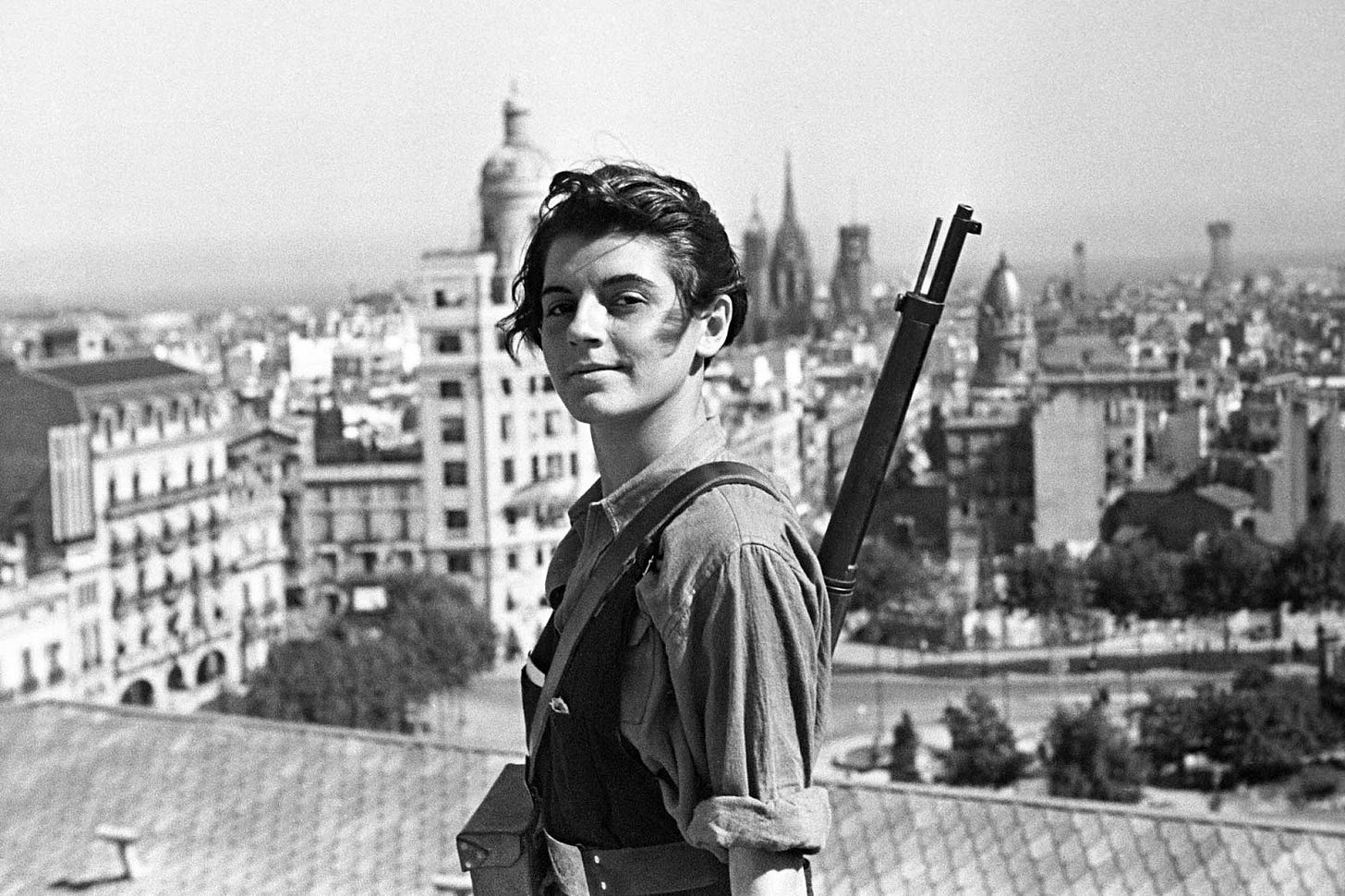

I can’t psychoanalyze figures of the past, but look at Orwell, who told us at the start of his time in the War he just wanted to be part, to take a stand. There’s a famous image of a woman named Marina Ginestà atop a hotel in Barcelona; she dons a rifle for Stalinist forces. She’s also just 17 in the picture. She looks bright and idealistic, but could she really have known what Stalinism meant?

And I look at young men today. When I first started making videos about the Spanish Civil War years ago, the battles over historical memory were mainly confined to places like Valley of the Fallen, mostly confined to Spain.

But the landscape has shifted since I last published on the War in 2017. A new generation of, I assume, catholic nationalists (Americans!) romanticize Franco's fascism with glossy videos and polished narratives. I don't want to name them because they seem young, but it's so odd. One video I came across explained that the reason the nationalists were good at fighting is because they were good Catholics. The republican fighters were godless atheists, so fought poorly due to fear of death.

(I wanted to be petty and reverse the argument: the godless Bolsheviks won the Russian civil war against the Whites because they wanted to make the most of this one life they had to live, and the Whites were too content to go to heaven.)

Another video listed bad leftist government policy before the Spanish Civil War, including letting women vote. You can criticize the republicans without being regressive.

But it’s too easy to just say the arguments of the Civil War era feel familiar. Spain was divided harshly by left and right and so are we. Political violence was normalized then and it's becoming normal now. Religion and “tradition” in government, or secular liberalism? Those parallels are too simple.

The real comparison, I believe, is the shared the lack of direction and meaning, especially for men, a deep sense of being lost with nothing to grab onto.

Witnessing it up close, seeing the shift today, it strikes me that the romanticization of the far-right of the past, or today’s predators (Tate) or nonsense esotericism (Peterson) - it comes from a place of despair. Old ways of finding meaning dissolve - so odd internet corners or even, to my genuine surprise, obscure Spanish fascism give a sense of identity and order. Something coded for your insecurity is better than nothing. It’s not material; it’s emotional.

And…it’s back. It’s here now, the sense that history sways on a hinge. The door isn’t closing; we can’t avoid what’s on the other side. We should walk through with our values clear. It’s not as simple as democracy good, fascism bad, though that’s undoubtedly true. The future we build needs to have meaning, not only opposition.

That’s the lesson of the Spanish Civil War I see for you and me.

That's why I’ve written a meditation on citizenship and uploaded a list of my favorite books on the Spanish Civil War:

Sourcing:

1. Hell and Good Company by Rhodes. 2015 https://amzn.to/3Zm5ysk

2. “The Spanish Civil War” by Hugh Thomas https://amzn.to/3Vqa7AD

3. Franco and the Condor Legion: the Spanish Civil War in the Air. Alpert. 2019 https://amzn.to/3OHMkby

4. Spain in Our Hearts: Americans in the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939. Hochschild 2017 https://amzn.to/3AYHqnG

5. World Without End: Spain, Philip II, and the First Global Empire. 2014 https://amzn.to/3CUF2id

6. José Calvo Sotelo La Real Academia de la Historia . Accessed Dec 3, 2024

7. “Frontline Madrid: Battlefield Tours of the Spanish Civil War” https://amzn.to/3Voye2K

8. George Orwell’s ‘Homage to Catalonia https://amzn.to/3D2eWtE

9. ‘For Whom the Bell Tolls’ by Ernest Hemingway https://amzn.to/4ijMxiZ

10. Niceto Alcalá-Zamora. La Real Academia de la Historia

11. Manuel Azaña Díaz La Real Academia de la Historia

12. “Text of New Spanish Constitution” Vol. 36, No. 3 (JUNE 1932), p374 accessed JSTOR

13. Azaña: Intellectual and statesman. Acción Cultural Española 2020 978-84-17265-16-8

14. Antony Beevor. 2006. The Battle for Spain. https://amzn.to/41nAds2

15. Non-Intervention and the Spanish Civil War. Thomas. ASIL Vol. 61 (APRIL 27-29, 1967)

16. The Barcelona May Days, 1937. University of Warwick. Accessed Dec 2024

17. JRR Tolkien and the Spanish Civil War. JMF Bru. 2011. Mallorn

18. International Brigades. Britannica. Accessed Dec 2024

19. George Steer and Guernica by Paul Preston. History Today Volume 57 Issue 5

20. “In Praise of...Guernica” The Gaurdian March 2009

21. The Telegraph “10 pieces of modern art that shook the world”

22. “The Art of War” by Colm Toibin for The Guardian. April 2006.

23. Howard University student Thaddeus Battle: 1938. Excerpted from the Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives, accessed via Flickr.

I enjoyed reading your article. Anthony Beevor’s book was my preferred. As a Spaniard living abroad and having the chance of seeing things from outside Spain, I would only add that the socialist government of Pedro Sanchez has been hellbent on re-opening those wounds. VOX is a consequence of that policy

clear parallels. question is - what could the precedent conflicts be today - Ukraine? Israel-Gaza? middle east volatility aka Syria, Libya?

another q would be how to categorize regimes with social democracy v. authoritarians and their records so far (win-loss)