Hong Kong Never Give Up! Indelible City Part 1

Prologue, Chapter 1

Let’s get started on our read-along of the book Indelible City. First, I’m running a Black Friday sale on paid subscriptions: 20% off, forever! ← This holiday season, I’m thankful to all who click and consider supporting this project to share knowledge of current events with a heavy pour of history.

Here’s the read-along schedule again:

Tuesday, November 26: Prologue and Chapter 1 “Words”

Tuesday, December 3: Chapter 2 “Ancestors”

Tuesday, December 10: Chapter 4 “Kowloon”

Tuesday December 17: Chapter 5 “New Territories”

Tuesday, December 24: Chapter 6: “King”

Tuesday, December 31: Chapter 7 “The First Generation”

Tuesday, January 7: Chapter 8 “Country” and Epilogue

If you’d like a refresher on the author or a bit of background of Hong Kong:

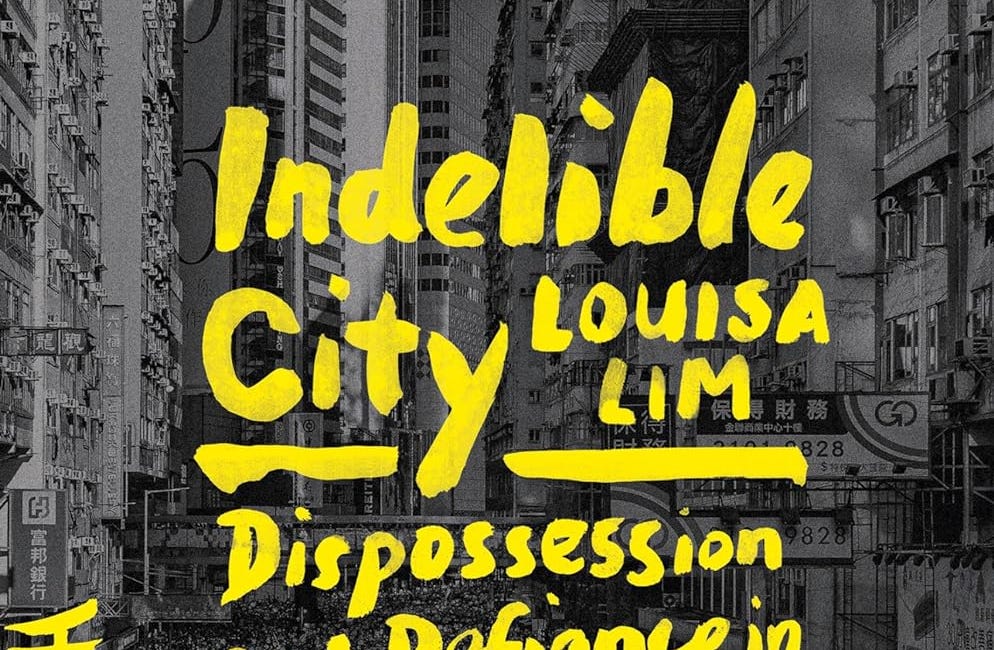

Our first read-along: Indelible City by 林慕蓮(Louisa Lim)

First, I’ve been having an absolute blast writing here on Substack. I’m not quite sure how, but there are already 1,000+ of you interested in learning about the present through the past at a thoughtful pace! I’m flattered by this, and excited to share knowledge openly.

Flipping the book open, the Table of Contents shows us the title of Chapter 1, “Words”, displayed in Mandarin as 字 (zì) . Now, you might already be groaning, “William, dude, you can’t get bogged down in the Table of Contents!” Forgive me.

However, the character, 字 (zì) , while functioning as “word” also translates to “symbol”, at least in my rudimentary knowledge of Mandarin coupled with an online translator (Lim gives etymology on page 17). The full sense of the character reminded me of the ebb and flow of the democracy movement in Hong Kong: at times it is explicit, loud; words are clear. But as we’ll learn, other times the movement must be near silent; the only way to know there is dissent in the city is to look for symbols clandestinely painted on walls. And since Mandarin writing is exclusively non-phonetic symbols, this seemed particularly poignant.

The author joins us in a note to explain that she spent her childhood in Hong Kong, but is not a native Hongkonger and no longer lives there.

I grew up in Hong Kong surrounded by a sepia tribe of Eurasians. -p28

“We were hybrids, Chinese Western concoctions.” —28

Lim also takes care to obscure the identities of certain interviewees for the book, as the Chinese National Security Law of 2020 is broad and can be applied backwards through time.

The Law passed in response to mass protests in Hong Kong in 2019 (though Beijing had wanted something like it for a long while). The Chinese central government wanted to ‘prevent, stop and punish’ demonstrations, something promised in Hong Kong’s Basic Law (Allen, 174). The ability to crush Hongkongers free expression was broad, essentially offering authorities a “blank check” to suspend habeus corpus, to end the autonomy Hong Kong expected after the handover from the British in 1997.

The height of those instigating 2019 protests is where Lim begins the Prologue. The rule of law is cracking in Hong Kong, as is Lim’s split identity as a journalist observer and invested Hongkonger. At once she wants to keep a distance, at the same time to join and defend the world she’s known.

For those who share knowledge as a mission in life, her struggle must ring true. Why share information if not to help build a better society? Thus, coverage becomes muddy.

Clichés like ‘hold truth to power!’ feel empty when expectations are to provide ‘both sides’ of every story, to follow the news-making happenings of the powerful as opposed to the doomed actions of the powerless. If a new law is proposed, does a journalist go to the halls of the legislature, or the home of the affected? Ideally both, but it’s not always an option.

And what if the legislation affects the ability to attempt objective coverage in the first place? What if even covering critique is seen as potential treason, secession? That’s how the 2020 National Security Law sees those who would film police brutality, or would climb upon a rooftop to witness graffiti art resistance.

The other challenge is that Hong Kong spent 155 years as a British colony (pg1). The colonizers neglected democratizing Hong Kong until it was clear the region would be returning to the control of China. Building a tradition from scratch would be a heavy lift.

Rereading chapter 1 and the story of the ‘King of Kowloon’, it occurs to me how much I prefer the scrappy imperfections of this Hong Kong artist over the polished resistance of Pablo Picasso.

Picasso painted Guernica to represent civilian bombings in a Basque town during the Spanish Civil War. The Germans were effectively practicing new terror tactics they would go on to use in World War II. Perhaps apocryphally, when asked by an SS officer “Who did this?” (‘this’ being Guernica), Picasso reportedly answered, “You did.”

I’ve always found Guernica and its backstory solemn and inspiring. I took a field trip with students to see it while living in Spain, solidifying its influence on me.

However, in the end, Picasso was painting from the relative comfort of Paris, far and away from the worst impacts of Franco’s fascism. Picasso was observing from a distance, and being a great artist, making something amazing. Manicured imperfection.

To contrast, the King of Kowloon graffitied tens of thousands of crude works, thus inspiring other resistance art in Hong Kong. His calligraphy was poor, at first glance the work seems to be scribbles. His imperfection is genuine, not innovation.

And importantly, the King did his work fearlessly, perhaps borderline obliviously. And he did it in the place he cared about, not far away.

In the end, it is the King’s persistence that stands out - free speech is voluminous in a free society; its value is taken for granted until it becomes scarce.

The King’s humble, ‘mediocre’ work might be ignored or forgotten in a free society. But in a place that’s lost its freedom of expression, his blasé is a reminder that the ordinary can be extraordinary.

See you next week for Chapter 2!

My video on Picasso’s Guernica:

1. Beijing Rules by Bethany Allen https://amzn.to/4fGbaEV

I was struck by Lim’s characterization of “The King” as shaman, truth-teller, and holy fool. I’ve heard of the idea of “holy fool” before but never in application to a real (non-fiction) person. Now I’m wondering about other movements with holy-fool-truth-tellers at their vanguard. (Truth in this case, being dependent on perspective.)